developing your unique value proposition & what is it ?

Anyone and everyone in business, politics, or public service should be able to answer the question, “What’s your value proposition?” It should always be unique to you or your organization. I sometimes call it UVP or Unique Value Proposition. It is applicable to someone looking for a job, for a company in search of new customers, and for a citizen assessing new community initiatives.

For example, in September of this year, the school system in my county will attempt to pass a 1-cent sales tax increase to help fund the building of new schools and to upgrade current schools. They are just beginning to communicate their value proposition to the community at large. With this referendum, the community should receive 20-30% of the tax revenues from people who do not live in the county, as their shopping in our county helps to pay for our schools. Additionally, the school system does not need to burden the community with additional debt by instituting a local sales tax. There are negatives as well, but a value proposition is, for the most part, intended to frame a persuasive proposition for someone to act the way you want them to.

I have been thinking about unique value propositions quite frequently these days as the topic comes up in my work on a routine basis. Many companies are interested in their unique value propositions to employees, customers, partners, and shareholders, as well as specific variations to each functional position (e.g., finance, marketing, operations).

Given the intense interest in value propositions, I want to address some of the dynamics and concepts in crafting a cogent value proposition. I also develop Unique Marketing Propositions and Unique Sales Propositions for clients. In this document, we will only discuss the UVP.

Definition of Terms

One definition that the American Heritage Dictionary provides for value is “Worth in usefulness or importance to the possessor; utility or merit.” One definition of a proposition is “the act of offering” or “that which is proposed or offered.”

As I wrote in another article recently published in a major bank’s corporate newsletter, value—like beauty—is often in the eye of the beholder (e.g., we each place slightly different importance or weight on things).

We typically associate the receiving of value as, in a civil case, a preponderance of benefits (i.e., at least 51% benefits and 49% costs), or in a financial sense, benefits minus costs = > 0. The terms benefits and costs include both tangible and intangible factors and thus need to be defined by the person receiving the benefits and paying the costs.

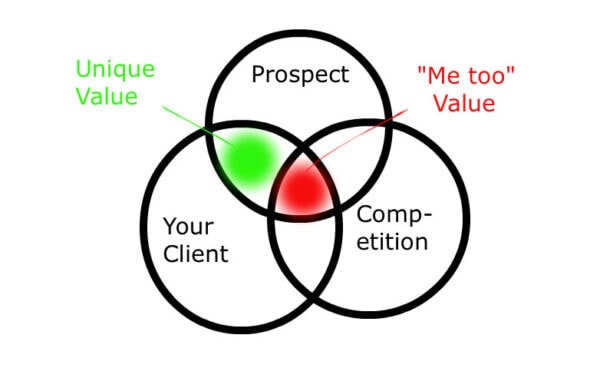

In essence, a value proposition is an offer to some entity or target in which they (the possessor) get more than they give up (merit or utility), as perceived by them, and in relation to alternatives, including doing nothing. In terms of form, a value proposition is generally a clear and succinct statement (e.g., 2-4 sentences) that outlines to potential clients and stakeholders a company’s (or individual’s or group’s) unique value-creating features.

Value Identification

At the end of the day, the real foundation of developing a unique value proposition rests on identifying and understanding what an individual or group values, which can be both stated and/or implied. For example, business executives can talk about integrity, honesty, and corporate governance all they want, but if their actions conflict with their rhetoric, we should look to what they actually do as a true representation of their values.

If a customer says the price is not important, but they continue to buy on price, the actuals should trump the intents. Questioning a conflict or inconsistency between what targets say they value and what they actually do can often help to uncover their real priorities and weights.

As in conjoint analysis, value is often evaluated in comparison to other items, criteria, and/or features. (Do you value A more than B, given these criteria and parameters?) Identifying and understanding value requires both context and perspective.

For example, a shareholder may view a reduction in force as a positive event, whereas an employee may view it as arbitrary and political, while a customer may view it as upsetting since they could lose their trusted account manager. As illustrated by the adage, “where you stand depends on where you sit,” knowing a particular group or individual’s perspective is crucial in understanding their specific value drivers.

As any good negotiator or salesperson will do, the essence of the value identification process is to perform a thorough needs analysis with the value proposition targets, be they employees, partners, or customers.

The needs analysis should cull out the value parameters (e.g., timing, magnitude, risk) and the current and anticipated pains and challenges of the individual or group. If your value proposition is analogous to a typical sales campaign, then you need to diagnose the different pains of your targets and understand which one hurts the most, and where they can get the “biggest bang for the buck.” Additionally, you need to understand the risks or side effects of your solution so you can either prevent or mitigate them, and develop, as necessary, the risk-adjusted value proposition.

Value Descriptions

In most value descriptions, there are both qualitative and quantitative components. A finance person (internal or external) may primarily describe value using some sort of Return on Investment (ROI) or Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) framework, whereas a customer may describe value as having greater status or looking better (e.g., focus could be functional, financial or emotional).

Economists often use the “willingness to pay” process as a way of quantifying what someone would be willing to pay to have “greater status,” for exampl

Each specific value description is a fact that must be understood in formulating the proposition. Once you understand how a group or individual describes the value, you will want to craft your language in a way that aligns with their terms and differentiates you from other alternatives. This practice of becoming “fluent” in a company’s or individual’s language is quite popular in sales, psychology, change management, and numerous other areas where you want to be seen as part of the group and on the “inside.”

As a value proposition is a form of persuasion, on a social psychological level, we are more easily persuaded by those who are familiar and/or similar to us, and thus using the same language or metrics is one way to establish that rapport (see neuro-linguistic programming for more about this area

Crafting the Value Prop (Determining Content) I use this type of format when working with clients to assist in understanding their VP – Remember it should be UNIQUE to your organization and not generic in nature.

1. Internal Analysis

· In looking at the value chain (internal logistics > operations > external logistics > sales and marketing > service), how does your company create value?

· What are your company’s core competencies and how do you differentiate yourself from the competition?

· What capabilities (internal and external—partners, alliances, joint ventures) can you bring to bear to execute against your value promise?

· Why should your value targets accept your particular offer (e.g., safer, better pay, more convenient, lower risk, etc.

2. External Analysis

· How do your value targets quantify (measure) the value that you deliver (e.g., how do you/they know when it’s a lot or a little)?

· How do you link your value proposition to your target’s needs and pains?

· How do you compare and differentiate the value that you deliver from the value that your competitors deliver (e.g., higher ROI or lower TCO)?

· How do you substantiate your ability to deliver on your value promise (e.g., track record, references, etc.)?

· How can you increase the return or decrease the risk, or both, in creating and delivering higher levels of value?

Conclusion

On the whole, there is no “silver bullet” when it comes to crafting a relevant, timely, and cogent value proposition given the dynamic nature of value, of the marketplace, and of a company’s capability set. However, it is also true that many companies—Volvo, for example—are not going to significantly shift their overall value proposition (i.e., safety at a premium) to the market given its intertwined nature to their brand and their core competencies. In the round, the value proposition concept is a valuable tool to utilize with each important constituency as it forces you to look both internally and externally in crafting a statement that is actionable by you and/or your company while being credible and compelling to your target audience.

Bill Simmel